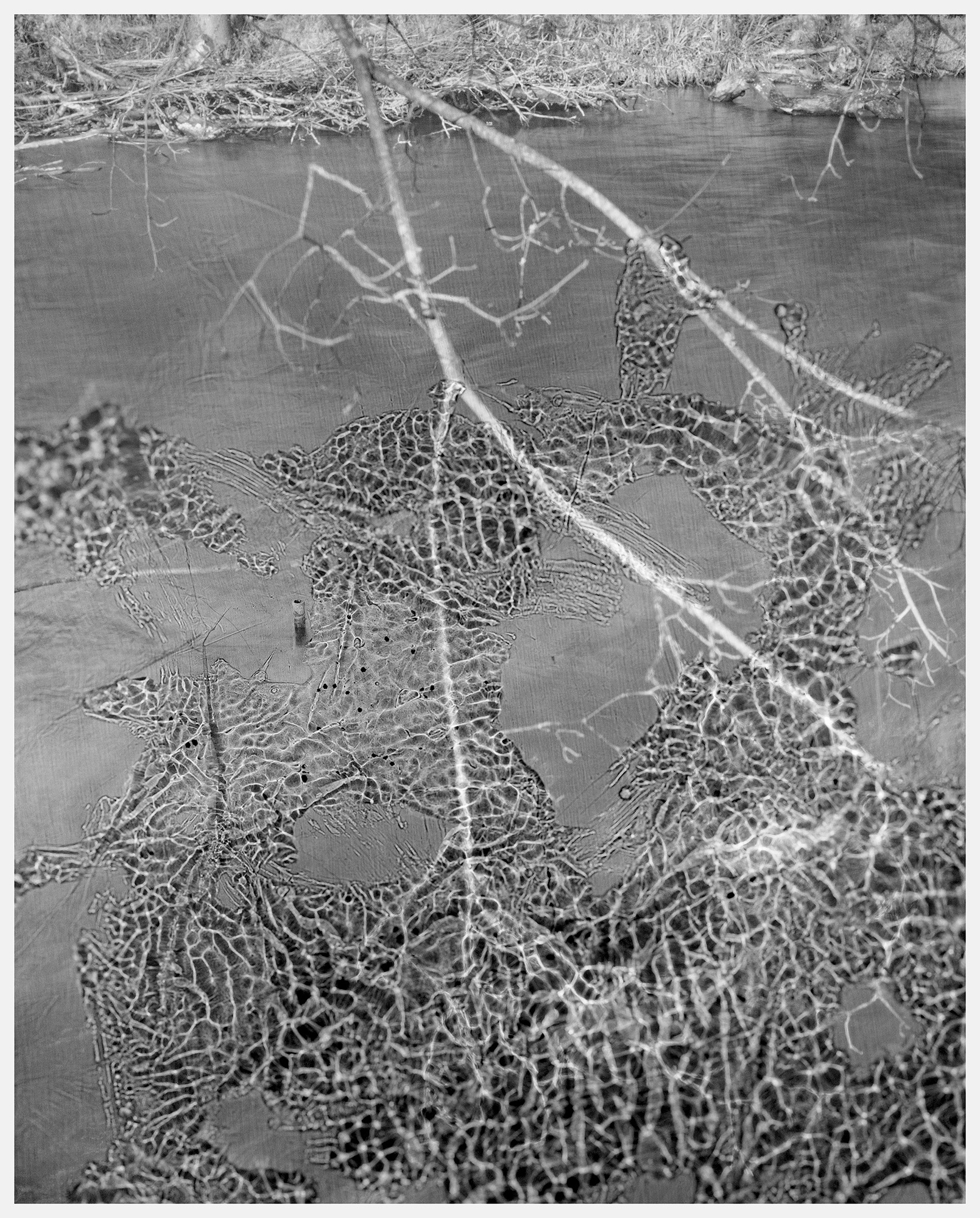

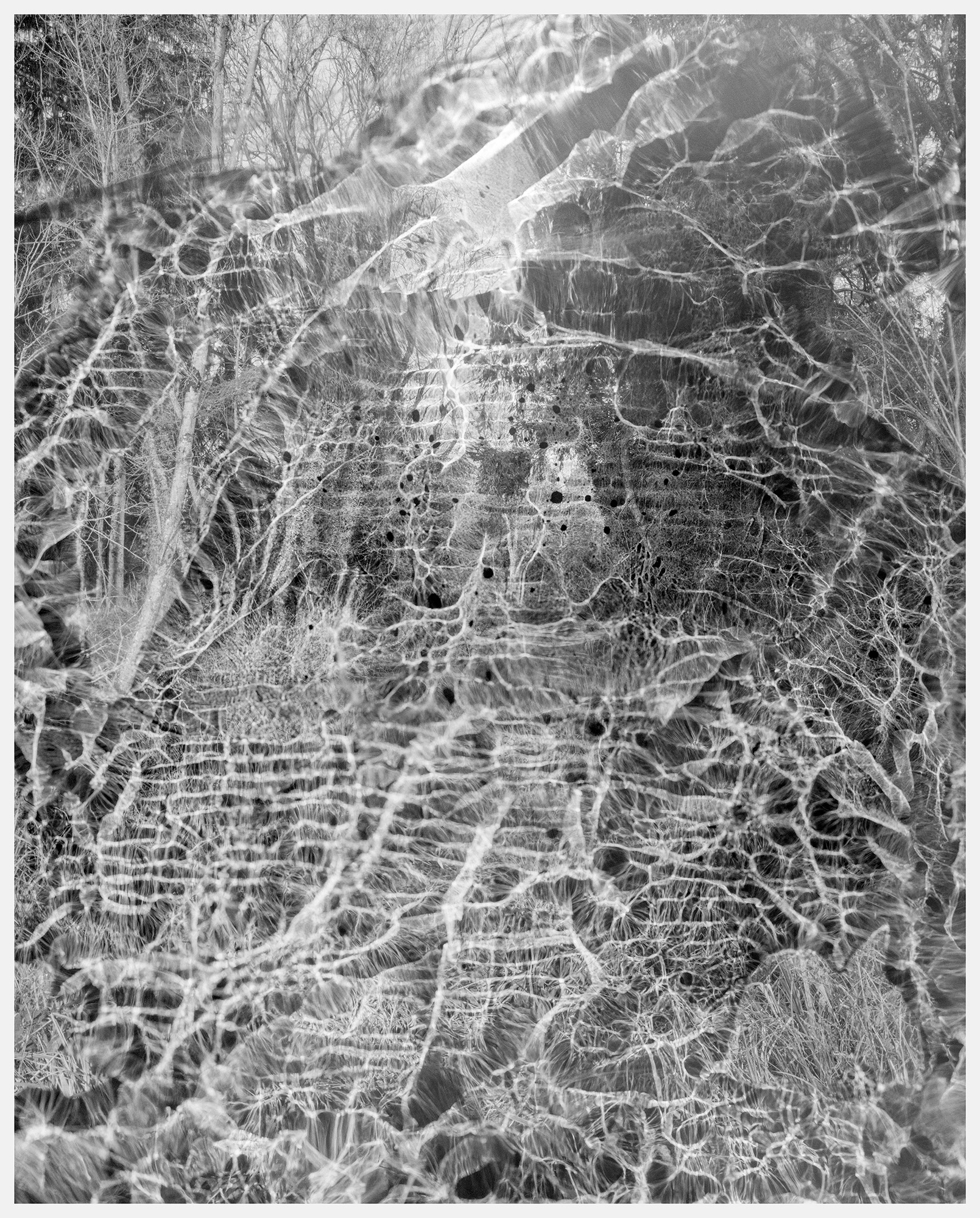

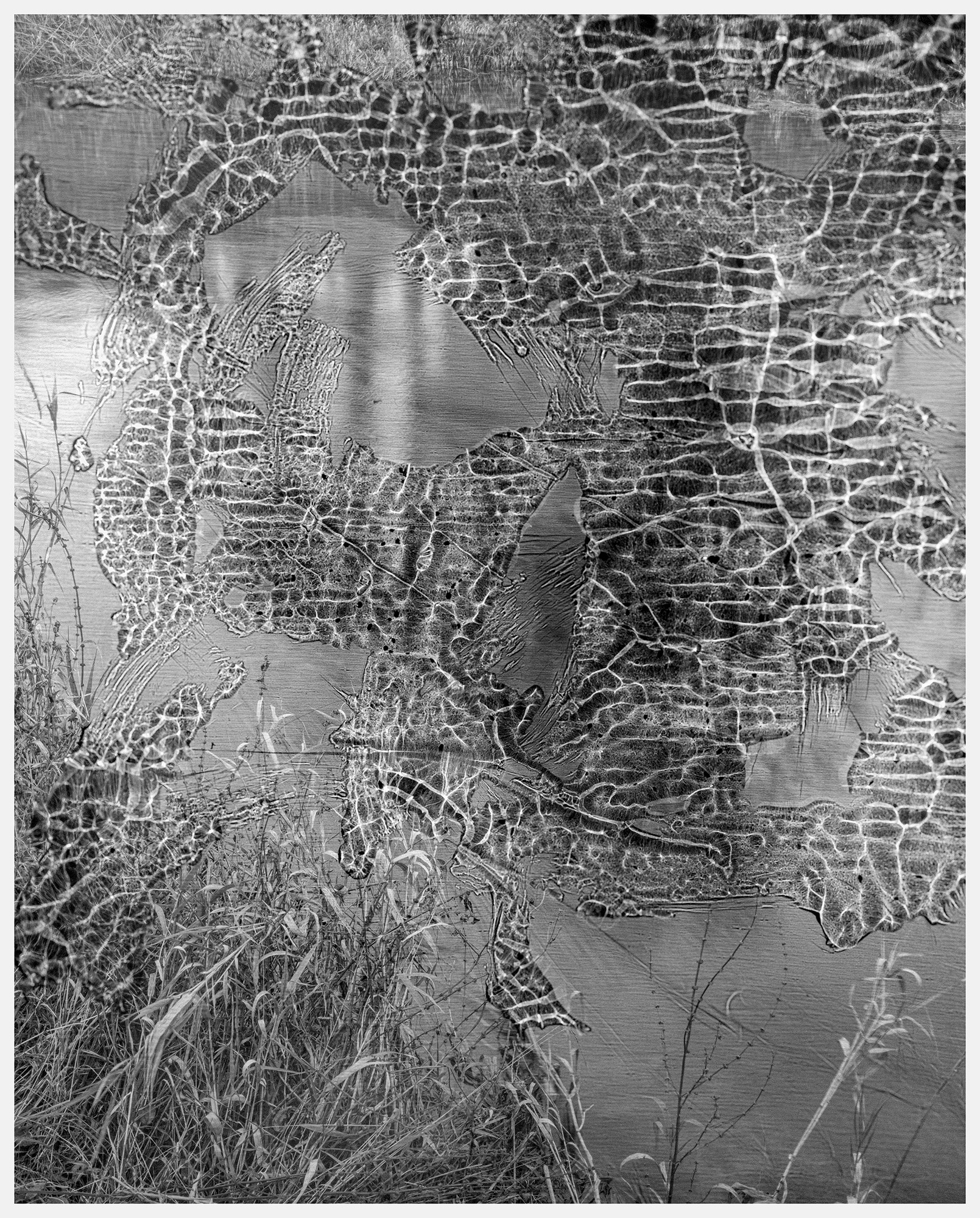

Mermaid’s tears → 2019

Photographs and essay

Photographs and essay

There is the common assumption that rivers are natural entities, part of pristine natural cycles and processes. But contemporary rivers are far from being wholly natural. On the contrary, for millennia they have been subject to extensive sculpting and shaping by humans down to the microscopic level. However, earlier modifications of environmental systems can hardly be compared to what has taken place since the beginning of the industrial revolution. With the ascension of modernity, in the case of water systems in particular, human-made non-degradable materials such as plastics have been widely distributed. They can be found as huge objects in the seven seas as well as in the tiniest currents in rural countrysides. As vastly distributed phenomena they challenge our concepts of the relationship between humans and nonhumans in the most fundamental manner. Recent considerations in the field of ecology postulate that the artificial border between nature and culture is questionable more than ever.

In his essay on plastic, Roland Barthes writes that “despite having names of Greek Shepherds (Polystyrene, Polyvinyl, polyethylene), plastic [...] is, in essence, the stuff of alchemy.“ He goes on to say that “more than a substance, plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation. [...] It is less an object than the trace of a movement.“1 Such a transformation reveals itself in the hands of humans; from an earthly matter to a human object. Barthes‘ words hold inherent the postulate that is increasingly represented today that is the questioning of the boundary between nature and culture. The case of plastic may indeed give some concrete expression to this consideration.

If we look at the history of the earth, plastic enters the stage of the earth very swiftly and at the same time, by now, it encompasses the earth completely. Its veil covers both the view of the present—the recording of the dissemination of plastic today—and the view into an unfathomable future. Plastic products are omnipresent and it is generally unimaginable to do without them. However, as early as 1972 the idea of plastic as a sterile, stable and benign material was radically questioned. At that time, scientists first pointed out that so-called microplastic “have bacteria on their surfaces and contain polychlorinated biphenyls apparently absorbed from ambient seawater”.2 They came to the conclusion that each such a piece of microplastic is in itself a tiny ecosystem, a plastisphere, home to “thousands of types of bacteria thousands of types of bacteria, diatoms, hydroids, eukaryotes and invertebrates“. The liveliness of microplastic has been studied ever since, but no conclusive implications for human life has yet been established. This seems besides the point, considering the manifold implications to marine life, due to suffocation and entanglement by larger pieces of plastics.

With this in mind, let’s return to Barthes‘ thoughts on transformation. Over time and under the influence of sunlight, the transformative nature of plastic causes larger fragments to dissolve into smaller microparticles. These particles—sometimes poetically called mermaid‘s tears—are smaller than five millimeters and take on their own life in the form mentioned above. The process of photodegradation disproves the long-lasting view of plastic as an irreducible product. What remains are microscopically, even nanoscopically small particles which are estimated to last for hundreds or thousands of years. As has been put elsewhere, “plastic objects are the cultural archeology of our time, a future storehouse of oil, and the future fossils of the anthropocene.“3 microplastics will outlast humankind and continue to live on as the perhaps defining object of our presence on this planet. It is at the same time a symbol of technological progress as well as that of untamed consumerism.

In order to understand microplastics as a phenomenon in the here and now, new concepts are needed that leave behind the age-old dualism of nature and culture. The philosopher and ecologist Timothy Morton proposes the concept of the hyperobject, a term he appropriated from computer science. With it, he refers to “objects that are massively distributed in time and space, ‘hyper’ in relation to some other entity, such as humans.“4 Thusly, hyperobjects, such as anthropogenic climate change or CO2 in the atmosphere, are so vast that they can never be grasped in their totality. Microplastics can be understood as such an object because we can only perceive it on a local level. We can conceptualize this object as a global phenomenon, but any attempt at a comprehensive and aesthetic perception is destined to escape us. It is not by chance that the most relevant phenomena of the Anthropocene mostly deny us their direct perception.

However, in order to adhere to the rising complexities of our time, new frameworks are of crucial importance. In conjunction with concept of the hyperobject, the artist and writer Susan Schuppli has proposed the notion of the material witness—a reference “to the double agency of matter as both harboring direct evidence of events as well as providing circumstantial evidence of the interlocutory methods and epistemic frameworks whereby such matter comes to be consequential.“5 Schuppli understands material witnesses as „nonhuman entities and machinic ecologies that archive their interactions with the world, producing ontological transformations and informatic dispositions that can be forensically decoded and reassembled back into a history.“6 That is to say that environments are engaged in practices of image-making and comprised of sensors that register external events as visible transformations. The planetary water systems are indeed full of such material witnesses. With microplastic, it is not only the case that as a witness it might be one of the most widely distributed, but also that it might figure as a prominent interlocutor on discussions of the nature-culture divide. This once human creation that is plastic, is now increasingly mutating into a hybrid of nature and culture, rendering obsolete the metaphysical boundary between the natural and the unnatural.

As was posited at the inception, an insistence on seeing rivers as either natural or artificial would be to reproduce entrenched dualistic frames of thought no longer applicable to understanding the hybrid entities of the Anthropocene. Rivers may instead be understood as complex entanglements of artificial and natural forces—hybrid forms that are neither natural nor cultural, neither human nor nonhuman, neither social nor material, but confluences or mixtures of all these. Such an understanding might take into account the complex nature of humankind‘s entanglement with natural processes.

References

1 Roland Barthes, Mythologies (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1972)

2 Carpenter, E.J., Smith Jr., K.L., Plastics on the Sargasso Sea surface (Science 175, 1972)

3 Pam Longobardi, “The Ocean Gleaner,” Drain (Junk Ocean), vol. 13, no. 1 (2016)

4 Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects (University Of Minnesota Press, 2013) 5,6 Susan Schuppli, Dirty Pictures (Living Earth Field Notes from the Dark Ecology Project 2014-2016, 2016)

1 Roland Barthes, Mythologies (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1972)

2 Carpenter, E.J., Smith Jr., K.L., Plastics on the Sargasso Sea surface (Science 175, 1972)

3 Pam Longobardi, “The Ocean Gleaner,” Drain (Junk Ocean), vol. 13, no. 1 (2016)

4 Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects (University Of Minnesota Press, 2013) 5,6 Susan Schuppli, Dirty Pictures (Living Earth Field Notes from the Dark Ecology Project 2014-2016, 2016)